Abstract:

Web-based social networks (WBSNs) are growing rapidly, and offer a tantalizing set of data for researchers. Not only are there millions of users and connections between them, but users are often allowed to augment their relationships with information such as type, strength, or duration. This paper sets out to present a comprehensive survey of these networks and their properties. We begin with criteria and definitions to determine which sites qualify for inclusion in this survey. After presenting categories, size, and other information, we discuss FOAF, a Semantic Web-based social networking initiative and discuss its role in the future of WBSNs.

1 Introduction

Web-based social networks (WBSN) have grown quickly in number and scope since the mid-1990s. They present an interesting challenge to traditional ways of thinking about social networks. First, they are large, living examples of social networks. It has rarely, if ever, been possible to look at an actual network of millions of people without using models to fill in or simulate most of the network. The problem of gathering social information about a large group of people has been a difficult one. With WBSNs, there are many networks with millions of users that need no generated data. These networks are also much more complex with respect to the types of relationships they allow. Information qualifying and quantifying aspects of the social connection between people is common. This means there is a potential for much richer analysis of the network.

As public interest in social networking has grown, the term “social network” has become looser. Many sites promote themselves as social networks when they do not maintain any data that would be useful for a network analysis. This chapter presents a set of criteria for qualifying a system as a WBSN and another set for determining when information can be considered part of a relationship. Those principles guided an exhaustive survey of existing WBSNs followed by a discussion of trends in social network data sharing on the Semantic Web.

2 Previous Work

This survey is motivated by the large body of work in social network analysis and in the study of online communities. While it would be impossible to cite all of the influential work related to social network analysis, the range of interest in the topic across nearly every academic field is impressive. These are just a few examples to give a sense of that scope.

Much of the foundational work in the analysis of social networks, and the major advances in the 20th century have been carried out in the fields of sociology, psychology, and communication (Barnes, 1972),(Wellman, 1982),(Wasserman & Faust, 1994). With a goal of understanding the function of relationships in social networks, and how they affect the social systems in which the networks exist, the research has been both theoretical and applied. Labor markets (Montgomery, 1991), public health (Cattell, 2001), and psychology (Pagel, et al., 1987) are just a few of the spaces where social network analysis has yielded interesting results.

In the last five to ten years, a new interest has developed in the structure and dynamics of social networks to complement the work already being done in social network theory. Though one of the first, and most popular papers in this area – Milgram’s “Six Degrees of Separation” study (1967) – was conducted by a social scientist, the topic is of increasing interest to physical scientists. Their studies have addressed issues such as mathematical analyses of the structure of small world networks (Watts, 1999), community structure (Girvan, Newman, 2002), and how social network structure affects the spread of disease (Dezo, et al., 2002), (Jones, et al. 2003), (Newman, 2002).

As the web emerged, online communities and social networks supported by the internet became a source of interesting data. Garton, et al. (1997) presented an excellent introduction to how traditional methods of social network analysis could be applied to these online communities. Work in this space was also embraced by the interdisciplinary field of human-computer interaction, which produced interesting work on designing and supporting online communities (Preece, 2000), their application to problems such as collaborative filtering (Kautz, et al., 1997) and electronic commerce (Jung, Lee, 2000).

The promise of social networks on the web is that they offer new opportunities to researchers across the board. With network topologies that can be automatically extracted from the web, the social networks provide a new, large source of data for the more mathematical and structural types of analysis. At the same time, users are participating in rich social environments online while building these networks. That holds promise for scientists interested in the general function of social interactions, and because the contexts of these social networks is often very restricted (e.g. business networking among Asian-Americans), they can serve as a window into specific communities

3 Definitions

There are many ways in which social networks can be automatically derived on the web: users connected through transactions in online auctions, users who post within the same thread on a news group or message board, or even members of groups listed in an HTML document can be turned into a social network. Many online communities claim to be or support social networks, but lack some of the properties one may expect of a social network. This work uses a very specific definition. A web-based social network must meet the following criteria:

- It is accessible over the web with a web browser. This excludes networks where users would need to download special software in order to participate and social networks based on other technologies, such as mobile devices.

- Users must explicitly state their relationship with other people qua stating a relationship. Although social networks can be built from many different interactions, a WBSN is more than just a potential source of social network data; it is a website or framework that has the development of an explicit social network as a goal. This criteria rules out building social networks from auction transactions, co-postings, or similar events that link people because the connection created as a side effect of another process.

- The system must have explicit built-in support for users making these connections. The system should be specifically designed to support social network connections. This means that a group of friends who each maintain a simple HTML page with a list of his or her friends would not qualify as a WBSN because HTML itself does not have explicit built-in support for making social connections. There must be some greater over-arching and unifying structure that connects the data and regulates how it is presented and formatted. 4. Relationships must be visible and browsable. The data does not necessarily have to be public (i.e. visible by anyone on the web) but should be accessible to at least the registered users of a system. Websites where users maintain completely closed lists of contacts are not interesting for their social networking properties – neither to users or people performing a network analysis – and are thus ignored for these purposes. For example, some websites allow users to bookmark the profiles of other users and others allow users to maintain address books. Even when these lists are explicit expressions of social connections, they would not qualify a system as a WBSN if they cannot be seen and browsed by other users. One important note here is that the system itself does not need built-in browsing support. Rather, each user’s data must be made accessible with unambiguous pointers to each social connection.

These criteria qualify most of the major social networking websites like Tickle, Friendster, Orkut, and LinkedIn while ruling out many dating sites, like Match.com, and other online communities that connect users, such as Craig’s List or MeetUp.com. Sites that require users to pay for membership are included as long as they meet the criteria above.

Within these social networks, users are often able to say more about their relationships than simply stating they exist. However, it is easy to confuse functionality of a WBSN with actual information about a relationship. Again, it is helpful to have a set of criteria that establish when an action or datum qualifies as information about a relationship in the social network.

- A basic social networking connection between individuals must exist before additional information can be added. Sites that allow users to rate others, such as rating someone’s appearance, often do not require that users have a connection – anyone can rate anyone else. In order to be used as additional information about a relationship, there must be a relationship between people in the first place. Thus, simple rating systems that do not require users to be socially connected are not counted.

- The information must be persistent. Many websites allow users to send messages or mini-messages (such as “winks” or “smiles”1 on dating-related sites). Since these are sent and do not persist as a label on the relationship, they are not a piece of information about a relationship. On the other hand, comments or testimonials about a person do persist on the website and are considered as free text descriptions of a relationship.

- The information must be visible and modifiable by the user who added it. At the same time, the information does not have to be publicly visible. Some data, like trust ratings, are personal and users would not want this shared with others.

4 A Survey of Web-based Social Networks

The goal of this survey was to profile every social network on the web that met the criteria above. The number of users and primary purpose of each website, along with what additional relationship information they support, if any, was gathered from each website.

This list grows daily and certain sites are not included because they are accessible by invitation only or in languages that could not be translated. An up to date list is maintained at http://trust.mindswap.org.

As of January 15, 2006 the survey encompassed 140 social networks with over 170 million members.

4.1 Size

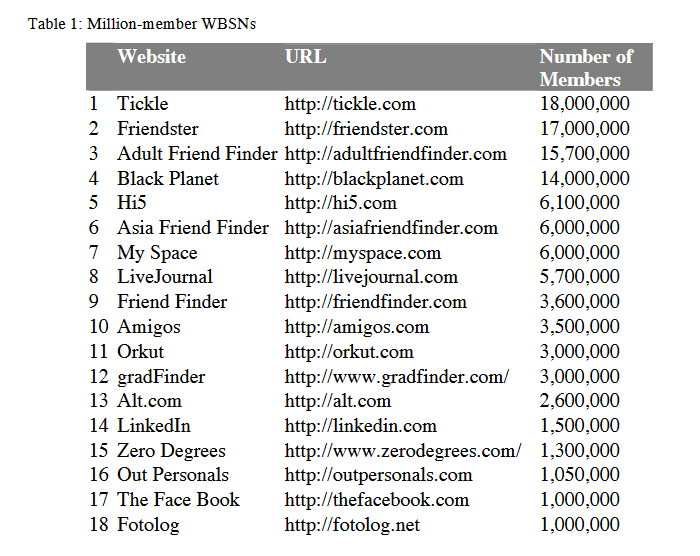

The size of the networks varied greatly. Eighteen sites have over one million members, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Million-member WBSNs

[Figure 1]

Figure 1. WBSN membership for sites ranked by population. Note that the y-axis is a logarithmic scale.

4.2 Categorization

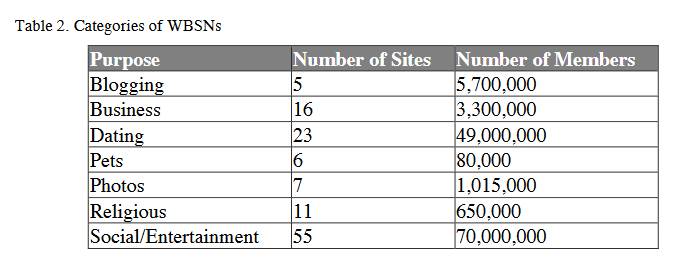

With only a few exceptions, WBSNs fell into a small group of categories, shown in Table 2.

Some sites fall into multiple categories (e.g. there are several sites that are both “Religious” and “Dating” sites), so member and site totals in Table 2 add up to more than the overall numbers.

Some sites fall into multiple categories (e.g. there are several sites that are both “Religious” and “Dating” sites), so member and site totals in Table 2 add up to more than the overall numbers.

Perhaps it is not surprising that sex and love play prominent roles among these websites. The “Dating” group is second in number of sites and membership only to the more general “Social/Entertainment” category. Seven of the eighteen million-member sites list dating or personals as one of their explicit purposes. Two of the most explicit dating sites fall into the million-member club: Adult Friend Finder (a.k.a. Passion.com), “The World’s Largest Sex & Swinger Personals site” with over 15.5 million members, and Alt.com, “the World’s Largest Bondage, BDSM & Alternative Lifestyle Personals.” At the same time, there is a continuum within these categories. At the opposite end of the spectrum is HotSaints.com, a site for single Mormons whose motto is “Chase and be chaste.” Religion and romance were actually tightly coupled among sites surveyed; half of the “religious” sites stated dating or personals as one of their primary goals.

4.3 Relationship Data

One of the primary questions motivating this survey was to see how WBSNs allowed users to add information about their relationships. Of the 125 sites found, fifty-four had some method for describing relationships.

On twenty-nine sites, the only method of describing relationships was through free-text comments or testimonials. With the exception of LinkedIn (a business site), all of those were dating or social/entertainment sites where testimonials generally took the form of friends writing about their friends. A random sampling from some of these pages included the following comments. Names have been changed to protect users’ privacy.

User X is my absolute favorite Pittsburgher. I refuse to go home to Pittsburgh unless User X is there to ease the pain of the awful big-haired reality that Pittsburgh is. I love User X a ton and am always interested to see what this girl is up to.

User Y, you can't have User Z. I love him too much. I too have hugged him and I never want to let go. He is my teddy bear and I want to have his babies. A little piece of me dies every time that I call and you don't answer. You know it was meant to be, you can't avoid the truth... Come back to me schnookums!!!!

Well everyone..this is my OLDER sister User M...wat can i say about her? hmmmz..well first of all...shes scary even tho shes like a million times shorter than me! =P..and shes really really really EMBARASSING! and she says im boy crazy..YOU ARE ER! *wink wink* newaiz gonna go now..b4 u can read this @ home.. Bubiez...love ya er..see ya @ home....dont hurt me =)

These examples are fairly representative of the set of free-text testimonials out there. They are amusing and offer entertainment, but from a computational perspective they are not useful.

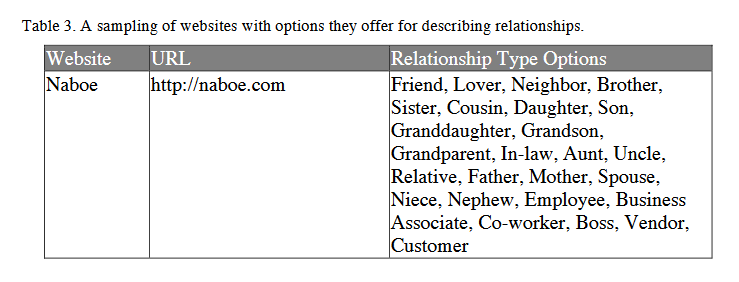

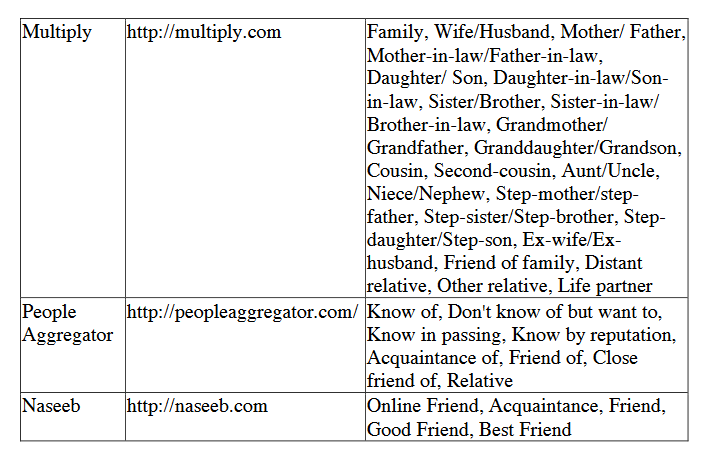

The other twenty-five sites that allowed users to describe relationships in a more restricted way. Twenty of them include options for users to categorize their relationships. Relationship types can be user-created labels in a few cases, but generally users choose from an enumerated list. Table 3 shows a few examples of these options.

These relationship types are much more useful when attempting to gain a deeper understanding of the dynamics within social network. Even when only a few options are offered, such as those from Naseeb seen in Table 3, the ability to approximately rank the strength of connections between people is greatly increased.

These relationship types are much more useful when attempting to gain a deeper understanding of the dynamics within social network. Even when only a few options are offered, such as those from Naseeb seen in Table 3, the ability to approximately rank the strength of connections between people is greatly increased.

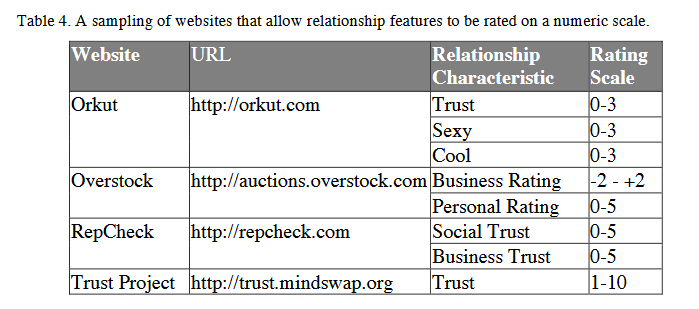

Other sites offer users the ability to rate aspects of their relationships on a numeric scale. Table 4 has a sampling of the features and rating scales available from some sites. From the perspective of someone performing a social network analysis, these numbers open up many new possibilities.

Analysis begins with the graph structure of the social network and using the rating numbers as labels on the edges. It is then essential to understand the functional properties of the relationship characteristic. Knowing whether the characteristic is symmetricbetween individuals, if it is transitive or composable, and other such qualities lead to the types of algorithms and mathematical methods that could be used to gain a deeper understanding of the indirect relationships between people in the social networks. Existing work that studies trust in social networks is presented in (Golbeck, Hendler, 2004).

Analysis begins with the graph structure of the social network and using the rating numbers as labels on the edges. It is then essential to understand the functional properties of the relationship characteristic. Knowing whether the characteristic is symmetricbetween individuals, if it is transitive or composable, and other such qualities lead to the types of algorithms and mathematical methods that could be used to gain a deeper understanding of the indirect relationships between people in the social networks. Existing work that studies trust in social networks is presented in (Golbeck, Hendler, 2004).

5 The Semantic Web and Friend Of A Friend (FOAF)

The 115,000,000 members of the social networks discovered in this survey do not represent 115,000,000 unique people. Indeed, one hundred accounts in that total belong to the author. Many people maintain accounts at multiple social networking websites. It is often desirable to keep separate information for business networking, connecting with friends and family, and dating. A person’s boss or colleague certainly does not need to know that he enjoys long walks on the beach…or any of the information one would provide while seeking a “discrete adult encounter”.

At the same time, users put significant effort into maintaining information on social networks. Multiple social network accounts are not just for compartmentalizing parts of our lives. A person may have one group of friends who prefer Orkut, another group on Friendster, like the quiz features of Tickle, and have an account on one or two religious websites to stay connected to that community. It can be desirable and convenient to join all of those connections together into one set of data. Friends who also have multiple accounts would be represented as a single person in this merged data set, and information about the user that is distributed across several sites also would be merged. The Friend- of-a-Friend (FOAF) Project is a potential solution to sharing social networking data among sites, and this section introduces how that is being done.

5.1 Background

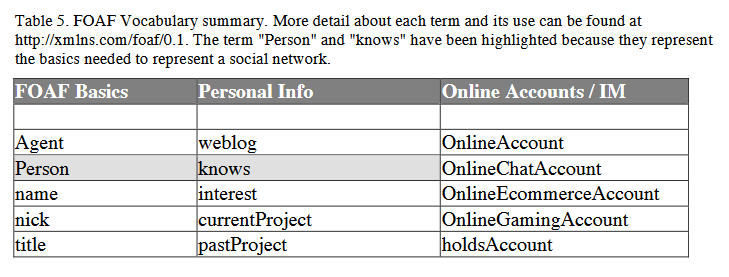

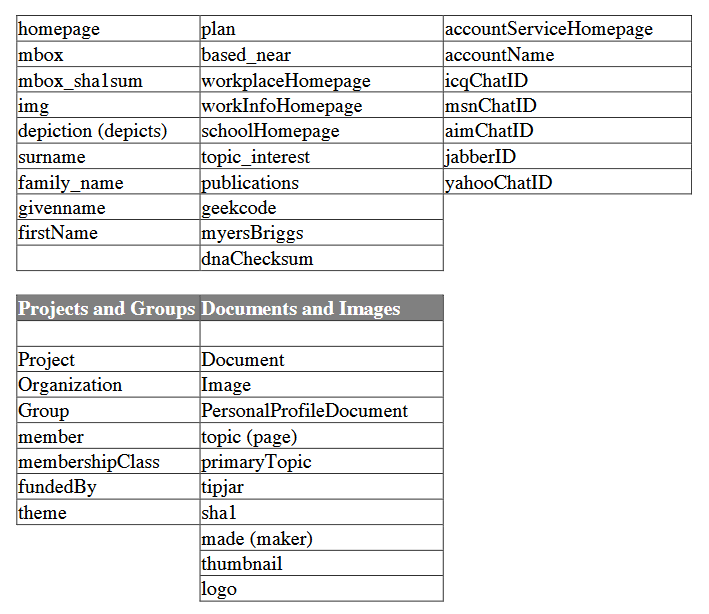

Rather than a website or a software package, FOAF is a framework for representing information about people and their social connections. The FOAF Vocabulary (Brickley, Miller, 2004) contains terms for describing personal information, membership in groups, and social connections. Table 5 lists the concepts and properties of the FOAF vocabulary. The property “knows” is used to create social links between people (i.e. one person knows another person).

The FOAF Vocabulary is represented as a Semantic Web ontology. The Semantic Web is an extension to the current web and is designed to encode information in a way that is machine readable. Like the current web of hypertext documents, Semantic Web information is maintained in documents stored on servers. Instead of using HTML, the Semantic Web uses a hierarchy of languages, including the Resource Description Framework (RDF) and Web Ontology Language (OWL). These languages are used to create ontologies, comprising classes (general categories of things) and their properties. The concepts from those ontologies are then used to describe data. There are several forms that data modeled with RDF and OWL can take. The examples presented here are shown in the N3 language. This shows the subject listed with each of its properties and their values.

In Table 5, terms with initial capital letters are classes, and terms in all lower-case are properties. A FOAF file will generally contain a Semantic Web-based description of at least one person with some personal information and who that person knows. The following code example contains a simple FOAF description of a person

:Joe a foaf:Person;

foaf:depiction <http://example.com/me.jpg>;

foaf:firstname "Joe";

foaf:lastname "Blog";

foaf:knows :Dan,

:K,

:Pi.

From this snippet, a program that understands OWL and RDF will be able to process the information. Using the FOAF vocabulary , it can recognize that there is a person named “Joe Blog” with a picture online who knows Dan, Pi, and K. Furthermore, links will commonly be included to the FOAF files describing Dan, Pi, and K.

The Semantic Web acts much like a large distributed database. There may be information about a person stored in many places. Using the basic features of RDF and OWL, it is easy to indicate that information about a person is contained in several documents on the web and provide links to those documents. Again, any tool that understands these languages will be able to take information from these distributed sources and create a single model of that person.

5.2 FOAF and Current WBSNs

If a website builds FOAF profiles of its users, it allows the users to own their data in a new way. Instead of having their information locked in a proprietary database, they are able to share it and link it. Some WBSNs are already moving in this direction. Six of the sites in this survey generate FOAF files for each user.

With this information, a user with accounts on all of these sites can create a small document that points to the generated files. A FOAF tool would follow those links and compile all of the information into a single profile. The code example below shows a file that would link a person to the files maintained at each of the sites listed in Table 6.

With this information, a user with accounts on all of these sites can create a small document that points to the generated files. A FOAF tool would follow those links and compile all of the information into a single profile. The code example below shows a file that would link a person to the files maintained at each of the sites listed in Table 6.

:Joe a foaf:Person;

rdfs:seeAlso

<http://trust.mindswap.org/trustFiles/385.owl>,

<http://www.livejournal.com/users/joeblog/data/foaf>,

<http://www.tribe.net/FOAF/6bed4755-a467-4fa9-844d-e9bfc786e570>,

<http://ecademy.com/module.php?mod=network&op=foafrdf&uid=71343>,

<http://joe.buzznet.com/user/foaf.xml>

<http://www.zopto.com/foaf.asp?id=10088>;

<http://trust.mindswap.org/cgi-bin/FilmTrust/foaf.cgi?user=joe>;

= <http://trust.mindswap.org/trustFiles/385.owl#me>.

These simple lines of code makes it possible to join potentially hundreds of pieces of information distributed across many sites together into one single description of the person.

Aside from the benefit to users who are able to merge their data, websites are also able to benefit from FOAF data on the web. For example, a website could suggest connections to other users in their system if FOAF data from another site shows a connection between the two people. Some user information could be pre-filled in if it is contained in a FOAF file somewhere else. By enhancing the user experience, a site becomes easier and more attractive to use.

5.3 Extensions to FOAF

While FOAF does have a long list of properties about people, many WBSNs have ways of describing people and relationships that are not part of the FOAF Vocabulary. One of the benefits of the Semantic Web is that ontologies and data can be extended by anyone, and thus it is easy to create properties that work with FOAF.

The Trust Project has created a Trust Module for FOAF that allows people to rate how much they trust one another on a scale from 1 – 10. Trust can be assigned in general or with respect to a particular topic. There is also FOAF Relationship Module (Davis,Vitiello, 2002) with over thirty terms for describing the relationships between people, including “lost contact with”, “enemy of”, “employed by”, “spouse of”, and others along those lines. While these modules are rather formal, any WBSN could define its own set of relationship terms or personal characteristics to include in the FOAF data about its users.

6 Conclusion and Future Directions

This survey of WBSNs was designed to provide a snapshot of the current state of web- based social networks, their number, size, and complexity. With this information, there are two clear fronts on which to progress: the computational and the analytical. The FOAF Project presented here is useful on both fronts in that it allows separate networks to be merged into one larger network model.

From the perspective of analysis, web-based social networks offer a look at a real living, evolving network. Users add, remove, and change connections frequently within these networks. The growth rate is exceptional, with larger sites gaining literally thousands of members each day. Tracking new members and their connections to the existing network at a regular interval would provide a window into how social networks grow and evolve. The information about relationships stored in many of these networks can provide an even deeper source of information, since the type of friends added to a person’s network can be tracked as well as if and when those relationship types change.

Jennifer Golbeck Web-based Social Networks: A Survey and Future Directions

Computationally, there are also tremendous opportunities. Particularly with information about relationships, there is space to develop new and useful algorithms for analyzing connections within the graph structure of the social network, making recommendations about indirect connections, and understanding the structure of relationships. Because many of the networks are open data sources, there is also the possibility of integrating users’ social preferences into applications. This rich web-based data source will form the foundation of this work in personalization and social intelligence within software.

References Barnes, J. A., 1972. Social networks. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Brickley, D., L. Miller,2004. FOAF Vocabulary Specification, Namespace Document, September 2, 2004. http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/.

Cattell, V., 2001. “Poor people, poor places, and poor health: the mediating role of social networks and social capital.” Social Science and Medicine 52(10):1501-1516.

Davis, I., E. Vitiello (2004. Relationship: A vocabulary for describing relationships between people, March 8, 2004. http://purl.org/vocab/relationship.

Dezso, Zoltán, and Albert-László Barabási,2002. “Halting viruses in scale-free networks.” Physical Review E 65 (055103).

Garton, L, C Haythornthwaite, B Wellman,1997. “Studying Online Social Networks.” Journal of Computer Mediated Communication 3(1).

Girvan, M, and M Newman, 2002. “Community Structure in Social and Biological Networks, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA.

Jones, James Holland, and Mark S. Handcock,2003. Sexual contacts and epidemic thresholds. Nature 423:605-606.

Jung, Y., A. Lee,2000. “Design of a Social Interaction Environment for Electronic Marketplaces.” Proceedings of Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, & Techniques 2000, 129-136.

Kautz, H., B Selman, M. Shah,1997. “Combining Social Networks and Collaborative Filtering.” Communications of the ACM 40(3): 63-65.

Milgram, S., 1967. “The small world problem.” Psychology Today 2, 60–67.

Montgomery, J., 1991. “Social Networks and Labor-Market Outcomes: Toward an Economic Analysis.” American Economic Review 81(5): 1407-1418.

Newman, M. E. J., 2002. The spread of epidemic disease on networks. Physical Review E 66 (016128).

Jennifer Golbeck Web-based Social Networks: A Survey and Future Directions

Pagel, M., W. Erdly, J. Becker,1987 “Social networks: we get by with (and in spite of) a little help from our friends.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53(4):793- 804.

Preece, J., 2000. Online Communities: Designing Usability, Supporting Sociability. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Watts, D., 1999. Small Worlds: The Dynamics of Networks between Order and Randomness. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K., 1994. Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wellman, B., 1982. Studying personal communities. In P. Marsden & N. Lin (Ed.), Social structure and network analysis (pp. 61-80). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Jennifer Golbeck Web-based Social Networks: A Survey and Future Directions